-

So long, old friend.

J Alfred Prufrock, according to TS Eliot, measured his life in coffee spoons. In common with most photographers, mine has been measured with cameras. I have said before that I am not an equipment freak, and that remains the case. They are a means to an end, and it is the end, the image, which captivates me.

But a curious set of circumstances in recent weeks has caused me to look back on my life as measured by the tools of my trade, and I thought it might make a good post. Besides, for some reason blogs about gear are always more popular than ones about pictures – read into that what you will.

It all began when my D3 failed to recognise my AFD lenses a couple of weeks ago. The lenses concerned worked fine with other cameras, so I knew it wasn’t them, and the camera itself worked fine with different lens types. As (bad) luck would have it, this all came about the day before I was due to shoot a big wedding. One of the affected lenses was my standard zoom, a 35-70 f2.8 AFD which I have used with every Nikon I have owned since about 1996. As a result I decided to hire an AFS 24-70G f2.8 ED for the day (since G lenses were unaffected by the problem) to get the wedding out of the way, before sending the camera into NPS for servicing. I fell for the hire lens, and started to think that I should upgrade anyway. It felt like infidelity not to mention extravagance, and I rejected the idea.

A couple of days later I got a call from a prospective new client, with the offer to meet to discuss a major assignment. I had an old friend and student of mine in the studio at the time, and she was asking me how I had got on with the hire lens. I told her about my adulterous feelings, to which she exlaimed “I’ll buy your old one from you!” I was stunned, and tempted. Very tempted. I suggested that if I got the assignment I had just been told about then I could justify the upgrade and I would sell her the lens.

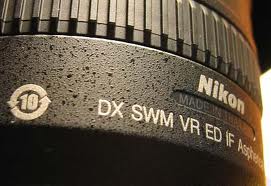

The “10” in a circle of arrows reveals something telling about the profligacy of modern society. I got the job.

I bought the lens.

While all of this was going on, I noticed a strange symbol on the underside of my AFS 14-24mm lens (which also exists on the 24-70 and no doubt many other new Nikkors), a “10” inside a circle of arrows. Apparently this logo indicates that Nikon expect that the lens will be “dumped” in about ten years time. Really? A £1500 lens dumped in ten years? Why? Now that’s extravagance!

It’s a precision optical instrument, which unless it is trashed will keep going pretty well indefinitely, surely? As I have already said, my 35-70 is already over fifteen years old, and I have many other bits of gear working perfectly that are far older than that. Perhaps with cheaper consumer lenses it might make some sense (only some, mind you). But the kind of lenses that serious photographers buy have a much greater lifespan, and more tellingly, while cameras might come and go, we tend to have a much closer relationship with our lenses than our cameras. They are our friends, our family. They are the ones through which we not only see the world, but through which we fix our vision, whether on film or sensors. They may become battered and worn, but we take to their idiosyncracies and adopt them as a part of our creative vision. That’s why it felt so disloyal to contemplate replacing a lens that has fixed tens of thousands of my images, and travelled with me all over the world attached to a myriad of different cameras.

So who am I? How did I get to be the person that I am now? The cameras that we use and discard tell us more about ourselves than we might think. Each of us has our own history. This is mine.

Minolta Autopak 430EX My first camera was a birthday present at the age of ten. A Minolta Autopak 430EX. It was a 110 format cartridge camera, and I vividly remember the very first photograph I ever took of my younger brother wrestling my Dad on the floor. I am not sure if you can still get 110 film, but I still have the camera, and I have fond memories of using it, and there are a few pictures I took with it that even with my greater experience I still think are pretty good. Needless to say it was fairly restrictive, and my love affair with photography did not start here.

When I was 18 I went on a two week tour around northern Italy with my classmates from school, an elongated bar-crawl loosely disguised as a cultural tour of Italian art treasures. I wanted to make sure that I had the capacity to record it as clearly as possible, so I borrowed my Dad’s Minolta SRT-Super with his 50mm f1.4 and 135mm f3.5 Rokkor lenses. It might appear disingenuous to include this camera in my list as it wasn’t ever mine, but this trip and the use of the camera was pivotal to the rest of my life, hence the reason for its inclusion.

Minolta SRT-Super My Dad was rather proud of his camera (I suspect this explains why the first camera he bought me, above, was also a Minolta) and he made me promise that I would not let it out of my sight. A marvel of mechanical engineering, it used matched needles for metering, and had a gloriously bright screen with the 50mm lens attached. I wasn’t so keen on the 135mm lens because it made the screen so much darker, which just shows how green I was that I didn’t understand the relationship between the maximum aperture and the brightness of the viewfinder. For that matter, I didn’t understand anything at all. I couldn’t figure out what the point of the depth of field preview was – it just made the viewfinder go dark!

Nevertheless, I heeded my father’s warning, and never let the camera out of my sight. On the third day of our trip, the coach we were travelling on was robbed while we were on the beach. Thirty-something people had their cameras stolen, except me, as I had it with me – not out of my sight. I ended up being given a load of film, and became the de facto “official” photographer. Out of five hundred photographs, only three didn’t come out. I thought I had a bit of a talent for this. In retrospect most of the photos were awful, but it was too late – I was hooked and determined that I needed to get myself a decent camera.

Minolta Dynax 7000i Perhaps unsurprisingly I was convinced that I had to get a Minolta, and at the time Minolta were at the vanguard of photographic advances forging ahead with the first usable autofocus SLRs. Their flagship second generation AF camera, the futuristic Dynax 7000i caught my eye.

I bought it at first with a 35-80mm f3.5-5.6, and quickly added a 70-210, a 50mm f1.4, a 28mm f2.8, and of course a flashgun. I had a system. I had no bloody idea what I was doing with it, but I was starting to feel like a photographer. However, something was missing. I needed a backup. I wanted to be able to have another camera which I could load with black and white film while the Dynax was loaded with colour. So I made possibly the strangest purchase choice in the history of poseurs trying to be photographers – or as the late Gene Nocon called them, fauxtographers – I bought a Minolta X700.

Minolta X700 It’s not that there was anything wrong with the X700, far from it. I think, in retrospect, that it is one of the best cameras they ever made. It’s just that with all the money I had spent on the Dynax it would have made sense to buy a body which fit that system. The X700 had a different lens mount and was completely incompatible, the only thing they had in common was the make. So I had to buy a lens for that too, another 35-70, which if memory serves me right had a continuous maximum aperture of f3.5 throughout the zoom. I also bought the motordrive, and later a Sigma 24mm f2.8.

Not long after I started university I met a fellow student and keen photographer called Roland. He had an F3HP, a Nikon. It had a grid screen, and an MD4 motordrive. I fell in love. In a curious way the Dynax for all its advances in techology was actually too restricting. The more I thought about the F3 and its bomb-proof build, the more I hankered for the creative release that I thought its simple controls would bring. I sold the

Nikon F3HP with MD4 motordrive and 50mm f1.4 lens Dynax outfit and found a mint second hand F3HP and an MD4 with a 50mm f1.4 AIS lens. It tells you something that the Minolta with four lenses and a flash only bought a camera and drive with a standard lens. I had moved from consumer gadget, to a proper image making tool, and for the first time I really started to spend more time thinking about pictures than the camera. I loved it’s heavily weighted and idiosyncratice metering. I understood how it “thought” and the HP viewfinder was like looking at an Imax screen.

Although I had always felt similarly about the X700 it pretty quickly dawned on me that it was mad to keep it. I now had the opportunity to build a system, and when my best friend and student film director offered to buy the X700 and lenses from me, I agreed, and put the money to an FM2 with an MD12 motordrive. Another Nikon, it could share the lenses with the F3, and as it was fully mechanical and didn’t require batteries it made a perfect backup body. At about the same time I bought a 24mm f2.8 AIS and a 105mm f2.5 AIS. The FM2 was new, but everything else was second hand. A word to the wise – the world is full of really good second hand gear. Don’t buy new unless you really have to. I missed the X700, but not as much as when my friend later told me he’d used it as a stake in a poker game and lost.

Nikon FM2 with MD12 motordrive I bought a Metz 45CL4 flashgun, a 180mm f2.8 AIS telephoto, and a 55mm f2.8 AIS micro (macro to every other manufacturer on the planet – I never understood why Nikon call them “micro” lenses) and my system was complete. I had no desire for zooms. I loved the simplicity and clarity of the prime lenses.

Yashica T4 All I needed was a small compact camera that I could carry all the time. For me the answer was a Yashica T4 – discreet with a good fast Zeiss lens.

Needless to say, it was not “all” I needed, because the more I learned the more I began to appreciate the massive difference in image quality that comes from making the jump to medium format. Just as I did with 35mm, I jumped too quickly and bought completely the wrong system. I was lured by a Bronica ERTS system including a couple of lenses and backs and various other gadgets.

Bronica ETRS Don’t get me wrong, it’s not a bad camera, but it was at that time the “consumer” option in medium format. At about the same time I started freelancing for a number of studios doing weddings and other things, and the limitations of the Bronica were all too obvious. I was attracted to the Rollei SLRs which were the first choice of the studio. They were rugged, simple, and ideal for the job, with a 6x6cm format compared to the Bronica’s 6×4.5. I don’t think I had the ETRS for more than six months before I sold it all and bought a mint second hand Rollei 6006 mkII with a standard 80mm F2.8 Planar lens.

Rollei 6006 mkII By now my skills had grown to the point that for all the beauty and simplicity of the F3 it was holding me back. I wanted something which could focus faster than me, and that something was the Nikon F5. I so desperately wanted to keep the F3 – I think it is honestly the only camera I have ever really “loved” – but I could not afford to keep it. I needed to sell it to finance the F5. I remember parting with it in a Hilton hotel to some guy who had answered my classified ad. “You’re sure it’s never been used professionally?” he asked. “No, not at all,” I lied. To be fair, compared with the way I hammer cameras now it was immaculate, but I did feel a pang of guilt, mostly because I wanted it to stay, not because I lied. I met a man called Mark in Victoria Station and parted with my cash to take his F5 from him, and a few days later I bought a brand new 35-70 f2.8 AFD zoom (the one mentioned at the start of this post) – autofocus and zooms were back in my life.

The Nikon F5 I had a falling out with my girlfriend. She left, and I thought about all the money I could spend on myself, so I promptly went out and signed on the finance dotted line, and committed to the biggest impulse purchase of my life, and something every serious photographer hankers after. I hankered too, and with no woman to waste money on, why not, I thought? I would devote my life to my first love and mistress: photography. I bought a brand new Leica M6 with a 35mm f2 Summicron. The girlfriend came back wanting reconciliation. I agreed, fool that I am.

Leica M6 Over time the manual Nikon lenses were sold, with the exception of the micro which I still use regularly as I never saw an advantage in autofocus for macro work. I replaced them with a 24mm f2.8 AFD, a 50mm f1.4 AFD, and an 80-200 f2.8 AFS, and extended my telephoto capability with a TC20EII teleconverter, effectively giving me a 400mm f5.6 AFS. The Metz flashgun was used exclusively with the Rollei, and a dedicated Nikon SB28 joined the system. The lenses may now all have been autofocus, but they worked perfectly with the FM2 – it was still a professional and integrated system.

The more I worked professionally, the more I used the Rollei for commercial work, but it wasn’t long before the need to crop the square images started to grate, and I invested in a Mamiya RZ67 Pro II system. Its unique revolving back, sharp lenses, and 6x7cm format which produces a near perfect 10×8 or A4 print without crop meant that the perceived increase in image quality was immense.

Mamiya RZ67 Pro II My love life had moved on. I met the woman of my dreams (although that rather crept up on me, I didn’t realise she was until about a year into the relationship) and we married. I took business more seriously, and since she was a photographer as well, I needed another camera to equip her to shoot for me. We bought a Rollei 6001 with another 80mm f2.8 Planar.

Rollei 6001 It was around this time that photography started to make serious strides in the digital world. I wrote occasionally for the Photographic Journal and the editor arranged for Nikon to send me their D100 to test. Ordinarily it would be wrong for me to include this in my list of cameras owned, but Nikon forgot that I had it for about a year, and I used it extensively. I experimented and found all sorts of ways that it was ideal for corporate and editorial jobs. Although I would not have used it for more significant commercial work, and certainly not for weddings or portrait work, I was still sufficiently impressed by it that when Nikon asked for it back, I went out and bought my own.

Nikon D100 Next there was a project I was working on that would mean extensive travelling and walking, and the need to keep my equipment light. Neverthless I wanted the quality which I knew I could only get from medium format, so I acquired a Mamiya 6MF medium format rangefinder. It is a testament to just how good this 6×6 format camera is that it is one of the few that has grown in value since I bought it. They are very highly sought after.

Mamiya 6 While many photographers were diving into the digital pool I was still reluctant to commit to using it regularly. It just lacked the quality that I wanted. There was the Canon EOS 1D series, and the reviews were very encouraging, but it was expensive, even without lenses, and I felt committed to Nikon. As far as I was concerned it was simply a matter of biding my time.

The Nikon D1 was a news tool, and not for me, and I felt the same when they released its successor, the Nikon D2H. But that all changed when they brought out the 12.4MP D2X. I tested the camera, and took unedited files to a professional printer where we could compare the output to prints from my medium format negatives. We were both astonished by what the D2X could do. I ordered one of the first to come into the UK – a hefty investment at over £3,500 for the body. Almost overnight my practice went from 80% film 20% digital, to 90% digital 10% film.

Nikon D2X It wasn’t an easy shift. There was a steep learning curve in post-production, and massive investments of time and money in upgraded computers, storage and back-up systems.

Nikon D200 Also the DX format of the sensor started to annoy me for its 1.5x crop factor – great for the telephoto stuff, a royal pain for the wide angle. I also needed dedicated flashguns, so a pair of SB-800s and a 16-35mm AFS were soon in the bag. The D100 was replaced by the D200, and after a while I was in my creative comfort zone again. With the advances that Nikon was making in iTTL dedicated flash I found it hard to believe that cameras could really get that much better at doing their job. I didn’t feel any of the “love” that I had felt for the F3, these were just tools, and the easier they made my job, the happier I was.

Toyo 5×4 large format monorail Creatively I was looking for new avenues and opportunities, and while the world moved inexorably down the digital expressway, I made a move into something altogether slower and more considered, and bought a Toyo 5″x4″ rail camera. This is photography for the perfectionist, and it taught me to think, really think, about why I wanted to take particular photographs. There is no way to hurry when there is only one frame, and when loading that sheet removes the means by which you can view the scene through the camera.

I have already said how comfortable I was with the D2X system, so much so that when Nikon announced the D3 even the fact of its full frame sensor (something photographers around the world had been begging Nikon to incorporate into any new professional body) was not enough to make me look at it more closely. I had only had the D2X for about two and a half years, and didn’t see myself making another big investment so soon. That changed when I saw some sample images taken at the world athletics championships in Japan… at 6400 ISO. It remains the only time in my life that I would describe my jaw as having dropped.

Nikon D3 with 14-24mm f2.8 AFS People who have only recently come into photography will not understand how revolutionary the D3’s low light capability was (and frankly, still is). In the days of film, your fastest – by which I mean most responsive to light – option was ISO 3200 film, which was in a word, crap. The price of high speed film was lack of contrast, lack of saturation, and grain like golf balls. Apart from the occasional artistic imperative, no one chose to use 3200 film unless they had no other option. The digital world started as a step backwards. Cameras were less forgiving of exposure errors (especially over-exposure), and anything much above ISO 640 was pretty well unusable. It wasn’t grain as such, but the digital equivalent called noise, and there are two types: luminance and chrominance. The former isn’t too bad if well controlled, the latter is bloody awful. Anyway, back to the point. The D3 suddenly offered the possibility of shooting at upto ISO 6400 with genuinely useable results. This represented a sea change in image making possibilities. I had to have one. I sold the D2X, got one of the first D3 bodies in the UK, and promptly spent a week photographing conferences in Barcelona and Madrid. I never set the ISO below 4000, and I was taking photos I had never thought possible.

The lenses changed over time. The 24mm was replaced by the astonishing 14-24mm f2.8 AFS, an SB900 became my main flashgun, working seemlessly with the two SB800s, and a huge commercial assignment requiring tilt/shift capabilities justified the acquisition of a 45mm f2.8 PCE lens.

Somewhere along the way I parted company with the Yashica T4. It seems odd in retrospect that I don’t know what happened to a camera. Did I lose it, sell it, give it away? I have no idea. But the absence of a compact had bothered me for some time. For all it’s flaws (and they are legion) the digital revolution’s most transformative effect was the chance to be far more experimental with one’s work than had been the case with film, but from a creative standpoint manufacturers had all but forgotten serious photographers with the compacts they were creating. In essence there were two fundamental problems: sensors which were too small and rendered results unsaleable if not unusable, and the absence of a viewfinder.

Fuji X100 I have said it before, but a camera is supposed to be an extension of your eye, and walking about like a zombie with your camera held at arm’s length is not intuitive. I complained on this blog, and gave a list of attributes I wanted to see in a decent digital compact. The response was almost universally “it can’t/won’t be done,” or “there wouldn’t be enough demand”. And then Fuji released the X100. I was right, the naysayers were wrong, and the X100 (and the X series it spawned) marked another turning point in cameras. The demand for the X100 despite many imperfections in its performance was huge. But Fuji was wise enough to listen to the feedback and release a series of firmware updates that addressed many of the key complaints. Naturally I put my money where my mouth was almost immediately.

Agfa Isolette Along the way I have experimented with many things, particularly old cameras. If you learn to accept their limitations and work within them you can have great fun and take some great photos. I don’t remember most of them, but I do have fond memories of an Agfa Isolette which I picked up from an antique shop in Greenwich about twenty years ago. No one would take you seriously with it, which allowed you to get in close, and the results (6x6cm medium format) on black and white film were really great – the lack of decent coatings on the lens was not so good for colour stuff. I still have it… somewhere, but for the life of me I cannot remember where I put it.

The D200 niggled at me. It was my backup camera, and if you are doing this for a living a backup is not an optional extra. But it bothered me that I had an expensive camera sitting in my bag almost never seeing the light of day. It gradually dawned on me that an ideal backup would offer something fundamentally different to the main camera. In effect it would have to have its own role and justify its existence in my life. The problem was that from my point of view no such camera existed.

Nikon D800 And then Nikon launched the D800 with its astonishing 36.4MP sensor. Here was a camera which was ideal for my studio and commercial work, but could play backup to the D3. It integrated with my system and offered something qualitatively different – the detail it is capable of resolving is as breathtaking (from a camera of this size) as the low light capability of the D3 had been.

Of course it wasn’t long before that resolving power started to show the inadequacies of my oldest AF lens, the 35-70 f2.8 AFD, which is where we started this post. I said goodbye to an old friend, and welcomed the 24-70 f2.8 AFS into my life. It is now responsible for most of the pictures I am making.

Of course, this is not the end of the story, merely a staging post and a chance for reflection. The D4 is on my horizon, along with the SB910, and a brace of other lenses. In time they shall pass too, leaving the images as the only things of permanence. It’s ironic that the fleeting transitory nature of time and experience is rendered permanent, while the physical objects employed in their capture come and go to be forgotten. I have affection for the occasional tool, especially the F3, but most are just that: tools of the trade.

As I said at the start, I am interested in pictures not cameras, but if you must measure me by the equipment I use, then this has been the measure of my life thus far.

CATEGORIES

- Book review

- Business practice

- Equipment

- Exhibition review

- Exposure

- Odds and ends

- Photographs

- Profiles

- Soap box

Recent Comments

Hi Nilu, It was published in 1999 in the Photographic Journal which was only a print publication at the time.…

Hello Michael, this was an enlightening article, thankyou for posting it. I was trying to find the original on the…

Thank you for the comment. Not practical at all in the rain, I agree. But if you spend all day…

A lovely photo Michael. A pair of old shoes can really convey so much character can’t they. Probably why Van…

My Instagram Feed

Tag Cloud

"we have no budget" art astronaut autobiography blog books Business practice cameras chaos clueless creativity death digital vs film doing it for free England Equipment funeral photography funny guns hell honours humanity know your worth large format lenses magnum man obsolesence people personal work photoessay portray prostitution publishing SEO stories stress environments students tv vanity publishing war website weddings whinge working

I worked for them part time in 2000(July) until 2001(May) and it was a really nice team to be involved…