The Rape of a Nation

BOOK REVIEW: Marcus Bleasdale – The Rape of a Nation

I started to write this review a long time ago, but somehow never managed to find the right way to pitch what I wanted to say. Recent events in India have brought the subject of rape to the fore of international consciousness, and now seems a particularly apposite time to finish what I started and bring this important book back to people’s attention.

Some people labour under the misapprehension that rape is about sex. Indeed, there have been a flurry of ill-informed comments on social media sites discussing the subject which peddle the tired notion that women have to take some responsibility for the way they dress. The suggestion is that if a woman is just too good looking some men cannot help themselves. If that were true, as a generalisation, then it would stand to reason that the majority of women who are raped would be glamourous, long haired and with beautiful figures.

They are not. They are not because rape is and always has been about subjugation. Girls, boys, babies, women, men, young, old, able, disabled, ugly, beautiful. All are and can be victims of rape. Rape is about power. It is about destroying a person mentally and leaving them diminished to live with what has happened to them for the rest of their lives.

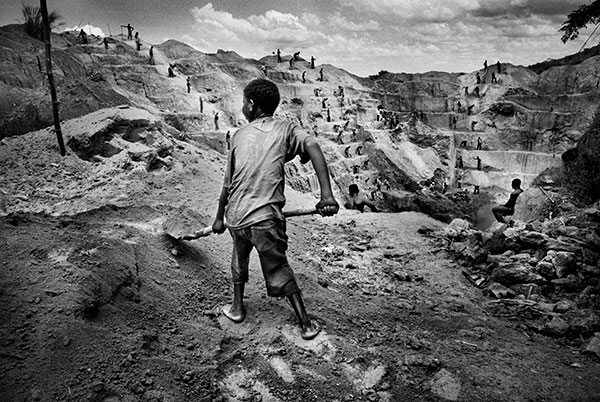

If ever there was a country that could be paired with the word rape, it is the Democratic Republic of Congo. One of the few remaining taboo subjects in the Twenty First Century, rape is so endemic in parts of Congo that statistically it could almost appear as a national passtime. But that is to make light of it. A weapon that is cheaper than bombs and bullets, it may not leave the victim dead but it certainly kills their spirit and robs them of a life they knew. Rape is recognised as a part of genocide when it is used specifically against an ethnic group.

Marcus Bleasdale’s most recent book is not about that kind of rape, although clearly it forms part of the background of the subject. The Rape of a Nation is about something more shocking, more horrific and beyond comprehension. It is about the defilement of an entire country; systematically; day after day, week after week, year after year, decade after decade. And we are all culpable. In his excellent foreword John Le Carré writes that “the continuing human tragedy of the Congo is not a statistic. It is a continuing human tragedy”. A simple statement – a brutal truth.

You don’t have to work as a photographer for long to know that for the uninitiated the job has an air of glamour about it, and this is particularly true for photojournalism. The poor cousin to being a Hollywood actor, Hollywood itself has done much to perpetuate this fallacy through movies like Salvador, and Under Fire. The reality though is far from glamourous.

With increasing frequency photojournalists have found themselves targets for protagonists who do not want their stories told, and even when they do not find themeslves directly in the line of fire, getting a story of consequence is often a lengthy and lonely affair. This might be worth while once the story is published, but that has often been harder than getting the story in the first place, something which has never been more true than now. Indeed, Neil Burgess famously stepped forward to call the time of death of photojournalism as 11:12 GMT on August 1st, 2010, although to be fair the late John Szarkowski called it around 1960.

So what is the relevance of this to Bleasdale and his book? It is two-fold: firstly the story itself is of enduring consequence. The problems so sharply conveyed in the book are as real and pressing now as they were when it was published. For that reason alone the delay in publishing this review is oxymoronically both irrelevant and relevant, since the story is still current and because the book is still available, and anything that can promote it to a wider audience can only be a good thing. Secondly Bleasdale himself is a photographer of consequence, and deserves to be taken perhaps more seriously than he has been in the past.

I once had a conversation with a commentator well regarded on both sides of the Atlantic in which Bleasdale was dismissed out of hand as “not to be taken seriously” for having been of independent means. It struck me as a remarkably stupid statement, and on the handful of occasions I have heard similar notes of dissent from others I have wondered why this myth perpetuates that for a photographer to be taken seriously they must be seen to be the starving type.

It is reasonably common knowledge that Bleasdale left his high-flying job in the city because he couldn’t bear the flippant attitude of traders to the misery and suffering of millions. When one of his colleagues openly wondered what the effect of a disaster would be on gold prices, Marcus had had enough. He walked out and changed his life for good. The fact that he has gone on to become one of the most highly respected photojournalists in the world and a full member of VII is a testament to his determination and skill. Frankly, if a man will stake his life and all that he has on something he believes in then it is worthy of our respect, and it is easier to stake everything if you have nothing to lose. That Bleasdale had so much to lose makes his choice the more remarkable.

His first book, One Hundred Years of Darkness, now out of print and very expensive if you can find a copy, paired his early images of the Congo with quotes from Conrad’s Heart of Darkness to celebrate the centenary of that great novel. It was a masterly piece of work, and a high-brow artistic endeavour: brilliantly conceived and universally well regarded, but also an exercise in historical introspection and literary allusion.

Where his first book was a Conradian journey of self discovery, The Rape of a Nation is unequivocally about the DRC, and in particular the people themselves. Just as importantly it demonstrates a breathtaking journalistic maturity. The images are undeniably Bleasdale’s, but he vanishes from the work itself, and allows the subject to be everything. Many photographers talk of wanting to give a voice to their subjects, and it is questionable how many succeed. In this case the success is emphatic.

The Rape of a Nation is meant to be absorbed. Just picking up the book you get a sense of the seriousness of the subject matter before you open its blood red cover. Gone are the artistic sensibilities of large format tomes, Bleasdale and his publishers Schilt opted instead for something the size of an academic text. There is no writing on the cover (excepting for the title and his name blind-embossed on the spine), instead the writing is saved to a black banderol which stands in stark contrast to the red board embossed with the stylised face of a leopard as seen on the coat of arms of the DRC. There is a particular irony in this choice of cover adornment, since the coat of arms in its full form also includes the national motto, made up of the three words: Justice, Paix, Travail. Justice, peace and work: the contents of the book suggest that there is precious little of the first two.

The reader opens the book to almost unremitting black. 240 black pages with 117 duotone images printed one per spread. While the images are captioned, there is another, more powerful, body of text. Lest the reader become too absorbed by his photographs Marcus chose to punctuate them with half pages of testimony from some of the people who feature. While writers might be given to rhetorical flourishes in an effort to introduce drama, they would fail utterly next to the simple statements of Bleasdale’s subjects which hit you like a brick. Choosing one at random:

The enemies attacked my village. They forced me to go with them, I stayed with them for many months. I was as a wife to them. Anyone could sleep with me. When I became pregnant I did not know if the time I gave birth was early or not. There was no hospital, no clinic, no doctor. When the baby came out the soldiers were using their hands to pull it from my womb. It was divided into pieces. They made me leave them after that and I had to find my way to the hospital fifty kilometres away. It took me many days.

Mushaki Miss P. Twenty three years old

Many great photographers produce work on hugely important subjects. But how worthwhile is it if most of the people who see that work and appreciate it are already in the know, or are photography junkies? Given the scale of the story in The Congo Bleasdale concluded it would be a spectacular waste of time, not to mention a pointless conceit, if the story was not placed directly in the hands of those with the power to affect change: the politicians, and the people who elect them. But targeting these two disparate groups poses different problems.

Bleasdale eschewed the bright lights of the mainstream and chose instead to work with Human Rights Watch, an organisation with which he has developed a close working relationship, and which has the capability of putting the work in front of decision makers. He personally put a copy of the book in the hands of Nane Lagergren, the wife of former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, and herself a UN lawyer. His thinking was simple: if you want to bring a story to the attention of the most powerful politicians, then bring it to the attention of those closest to them. It’s not that Marcus has anything against newspapers and magazines, on the contrary versions of the story have been published all over the world. Rather it is that he recognises the limitations of relying on them as the only means of disseminating his work.

As a consequence Bleasdale has come to question more directly why he does what he does. What is it for? Who is it aimed at? What difference can it make. Photojournalism may not be what it once was, and though a entire treatise could be written on that subject alone, there is one element of that perception which is worthy of deeper consideration, and there is no doubt that Bleasdale gave it plenty of thought. That element is knowing your audience.

While politicians and industrialists may read papers and magazines and meet with representatives of pressure groups, the people who elect them and buy their products increasingly do not. Bleasdale was struck by the numbers of young people who do not read papers, but do consume their news in other less traditional ways. Always looking to find new methods of expanding his audience, he took the unusual step of collaborating with Christian Aid’s youth collective Ctrl+Alt+Shift and artist Paul O’Connell to turn his images into a powerful comic strip which was published in Ctrl.Alt.Shift Unmasks Corruption. He collaborated with Mediastorm to create a multimedia publication which is also available as a DVD. These are not distractions: to put it simply The Rape of a Nation is one of the most powerful bodies of photodocumentary of the last decade, and whatever format you use to absorb it, the story is searing and shocking, but it is conveyed with skill and empathy by a talented man who clearly cares for and about his subjects.

For years the Democratic Republic of Congo has been systematically raped of its resources while the rest of the world looked the other way. A country which ought to be by virtue of its abundant natural resources one of the richest in the world has been reduced to a kind of hell on earth. Thousands (not an exaggeration) die every day in the DRC as a result of disease and malnutrition, wrought by unending corruption and warfare. And yet, what shines though Marcus’ images is a lust for life in the people of this country. Caught in the crossfire of warlords and corporate greed, the Congolese have a spirit that shines through the darkness that affects them daily. It is a spirit which Bleasdale also gives voice to, and in so doing demonstrates that the richest resource of all for the Congolese is the people themselves. We in our cosseted lives in the West owe it to them not to turn our gaze, however much it pains us.

The Rape of a Nation – Marcus Bleasdale, Schilt Publishing, 117 duotone photographs, 240 pp, 36 half-size text pages, Hardback with banderol, €39.90, ISBN 9789053306710

Leave a Reply