What’s in a box?

The news today is dominated by talk of an impending vote on cigarette packaging, and more specifically on making it plain. But if we are being honest, describing the proposed packaging as plain is at best disingenuous. As far as I am concerned, this is plain cigarette packaging:

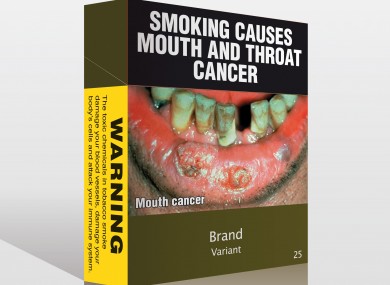

However, the intention is that “plain” packaging will look something like this:

It is amusing to listen to pro-smoking lobby groups argue that “plain” packaging won’t make any difference to smoking uptake by the young, while the advocates for the change argue equally vociferously that it will. Both of them are lying, but for very different reasons. Starting with the tobacco companies, if their argument was correct you would have to ask why historically they all invested so much time, energy and creativity into their packaging, advertising design and branding. My suspicion is that they would be only too happy to settle for truly plain packaging (see my example at top), since they know it would have little impact on their overall sales and market share. Meanwhile the legislators and anti-smoking lobby are quick to say that packaging and branding influences the young and persuades them to start smoking, and that for that reason they need to have an “anti-branding” campaign (against smoking per se rather than a specific manufacturer or brand) to scare the daylights out of people based on the impact it might have on their health.

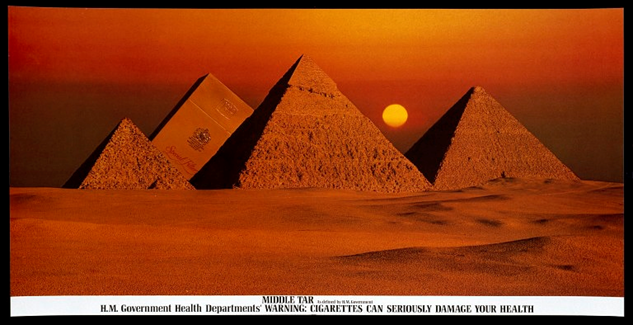

The great thing about being an adult is that you were once a youth yourself, and if you try hard enough you can remember exactly how you felt about things and reacted to them. So here is something I remember very clearly from my youth, an advert for Benson and Hedges:

I was at boarding school at the time, and I remember a friend, Kevin, sticking this picture up on his wall (along with the many others that the brand released over the period). I thought that this was so cool. Did it make me want to smoke? No, it made me want to be a graphic designer or a photographer (funny that – perhaps it was cigarettes that got me into what I have been doing for the last 20 years!). Did this advert make any of my friends want to smoke? No. It may well have influenced what brand those who did smoke chose to buy, but none of the very clever advertising of the time compelled people who didn’t light up to start. But to be fair the prevalence of cigarette advertising and the ubiquity of people smoking will have influenced a lot of teenagers into thinking that it would be OK if they did. Society did not treat smokers as pariahs in the way it does now, and there can be little doubt that alone has had a huge impact on persuading many never to take it up who might otherwise have done so. But the fact is that some people will always choose to smoke anyway, just like some people choose to take drugs. Indeed it can be the very illegality of it which creates an appeal that is unavoidable. As a result, a part of me wonders whether the “plain” packaging proposed might be less effective than genuinely plain packaging. After all, there can be very few people who are not totally aware of the negative effects of smoking on health, and from the point of view of teenage rebellion, nothing is more of a turn-off than bland.

What’s my point with all this? Partly it is wondering where the limits of state interference in people’s lives should be. Yes, smoking is harmful to your health, but it is still legal, as are many other things which are also harmful to your health. Are we going to go the same way with alcohol? What about sugary products? How about driving – should cars be “plain” by which I mean emblazoned with pictures of contorted bodies of people killed by not being careful enough? What about extreme sports? At what point are my choices MY choices, and is it time for the government to back out and leave us to live our lives as we choose? Increasingly the bean counters are looking to tighten everything to reduce the burden on the state, and while that is understandable surely there must be limits?

I am not a smoker, and I support the legislation that has been enacted over recent years. I love the fact that I can breathe in a pub or restaurant and not come home smelling like an ashtray after a night out. I would not like my own children to start smoking and the overall move to reduce its visibility and therefore acceptability is welcome. But if within this prevailing climate a free person chooses to smoke who am I to castigate them?

One sad part of all this is the effect on creativity within the industry. Cigarette packaging has a long history of great design, and the skill of the artists and designers over the years has been to tap into the prevailing zeitgeist and both reflect it and shape the styles of the times. To work on a small space and create something which reflects society and its sensibilities and fashions is a fabulous skill, one which has now been replaced by proscription and fear. It is a dying art and the death is happening elsewhere for different reasons too – think of the record or CD cover, slowly becoming irrelevant in the era of the digital download.

Photo: © Michael Cockerham 1992

The real reason I started this post is that the news reminded me of a grave I happened across about a year ago. Hidden in the undergrowth of the cemetery of St Mary’s Church in Bexley, less than a quarter of a mile from where I am sitting as I write this, is the headstone above a different box: the coffin of Walter Everett Molins. The headstone was so unusual that despite its hidden position I was convinced he must be a man of some significance, so I took a photo and looked him up.

Molins was born in New York, the son of Jose a Cuban who made cigars and hand rolling cigarettes in Havana in 1874. Jose came to London after a period in the US (when Walter was born). In 1911 Walter and his brother Harold invented a machine which could make almost any type of package, and in 1912 they set up the Molins Machine Company. In 1924 their Mark 1 machine was making 1000 cigarettes a minute and by 1931 they had also set up in Richmond, Virginia: the heart of the US tobacco industry. Walter invented a number of machines and packages for the tobacco industry, the patents for which still exist today, and indeed it was his son, Desmond who having joined the family business invented and patented the hinge-lid pack in 1937 that is so ubiquitous today, and is the basis for all the discussions about the design which should or should not exist upon them. Interestingly Philip Morris relaunched the Marlboro brand in 1954 using the Molins’ designed pack, and it was instantly successful with a 50 fold increase in sales. Perhaps the legislators should be looking at the physical design of the cartons rather than what is printed upon them!

What, I wonder, would Molins make of the discussions today? He is quite literally the father of the modern cigarette pack, but he was an engineer at heart, and no doubt he would simply have worked the problem like all engineers do. The company he created still exists today. Molins PLC had sales of £105.2 million in the year to 31 December 2013, with bases in the UK, the US, Canada, Holland, Brazil, Russia and Singapore. Not bad for figuring out how to pack a few fags.

Leave a Reply